Table of Contents

Introduction to part 2

In this series of three articles several of Carl Jung’s most important concepts in relation to the contents of the Psyche are defined and discussed. In the first part I have discussed the more conscious parts of the psyche; the ego, the self, and the persona, whereby parts of the self and the persona are already, depending on the individual, unconscious to a certain degree. In this second article, some of the more unconscious parts of the psyche are explored; the unconscious itself, the archetypes, and the soul. Later, in article three, the more ‘dangerous’ and hidden aspects of the psyche are addressed: the shadow, the anima, and the animus. It is the purpose of this series of articles to make these concepts more relatable, therefore a business is used as a metaphor for these concepts.

Parts of the content of these articles are based on the content of my book: Carl Jung and the Rebirth of the Soul. In case you want to explore these concepts further then this book might interest you as well.

The Unconscious

In part 1 we have seen that parts of our conscious self are largely at the mercy of our unconscious, at least as long as we have not made the unconscious conscious. It is therefore important to define what the unconscious is. To make matters a bit more complicated, however, Jung further divided the unconscious between the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious.

On the one hand, according to Jung, the personal unconscious consists of events which have occurred in an individual’s life but have not been perceived consciously. Although these events have occurred and have had a certain impact on the individual, they have, as Jung observed, only been perceived unconsciously, and have therefore remained under the radar of our consciousness: “There are certain events of which we have not consciously taken note; they have remained, so to speak, below the threshold of consciousness. They have happened, but they have been absorbed subliminally, without our conscious knowledge.” (Man and his Symbols, p.5)

However, although these events may not have been perceived consciously by the individual, they can still have an undeniably strong influence on the behaviour of an individual. In the case of our business example introduced in part 1, this can be compared to events occurring within the personal lives of the employees of the company. These events might impact the way in which the employee conducts his or her business, without the CEO being aware of the events in the employee’s personal life. For instance, if one of the employees is having relationship problems, he or she may not communicate about this to the CEO, however, at the same time, it might influence this employee’s performance at work. It is only by building a good relationship with this employee (personal unconscious), that the CEO (the ego) might come to understand why the employee is not performing as well as he or she did before.

On the other hand, the collective unconscious is the part of the unconscious with which an individual is born, according to Jung. As a result, as opposed to the personal unconscious, the collective unconscious is not dependent upon the personal development of the individual: “A more or less superficial layer of the unconscious is undoubtedly personal. I call it the personal unconscious. But this personal unconscious rests upon a deeper layer, which does not derive from personal experience and is not a personal acquisition but is inborn.” (The Archetypes and the collective unconscious, p.3) As opposed to the personal unconscious, Jung considered the collective unconscious to be universal because it is similar within everyone. It can be defined as a layer hidden deep within the psyche which is present within everyone’s unconscious: “It has contents and modes of behaviour that are more or less the same everywhere and in all individuals. It is, in other words, identical in all men and thus constitutes a common psychic substrate of a suprapersonal nature which is present in every one of us.” (The Archetypes and the collective unconscious, p.4)

In the case of our business example, the collective unconscious can be compared to a certain working environment which has developed overtime within a business. Although this working environment has a significant impact on the way in which the business operates, often no one is consciously aware of the existence of such an environment, and it is not easy to define when and where the development of such an environment has occurred exactly. In case the working environment is developing in the wrong direction, thereby resulting in a negative working environment, it is often only discovered when it has already become too difficult to change it. When a new employee joins the company, he or she will then often unconsciously blend into such a working environment as well.

Although Jung considered the unconscious to be of extreme importance, the existence of the unconscious has not been accepted by everyone. Jung observed that numerous philosophers and scientists have dismissed the existence of the unconscious, both personal and collective. Jung indicated that the notion of the unconscious is often dismissed because it would suppose the existence of more than one personality: “They argue naively that such an assumption implies the existence of two “subjects”, or (to put it in a common phrase) two personalities within the same individual.” (Man and his Symbols, p.5)

However, instead of disagreeing with such a notion, Jung claimed that this is exactly what the existence of the unconscious implies: the existence of two personalities within one individual. The existence of this divided personality is not caused by mental illness, instead, Jung argued that each and every individual is affected by such a reality. However, at the same time, the existence of multiple personalities does not necessarily have to be an issue, as argued by Jung: “It is by no means a pathological symptom; it is a normal fact that can be observed at any time and everywhere. It is not merely the neurotic whose right hand does not know what the left hand is doing” (Man and his Symbols, p.6) Jung believed that this situation is inherent to the existence of the unconscious: “This predicament is a symptom of a general unconsciousness that is the undeniable common inheritance of all mankind.” (Man and his Symbols, p.6)

However, although we are often unaware of these unconscious forces, Jung believed that it is possible to integrate these forces, thereby making them conscious. As a result, problematic situations resulting from the existence of these multiple ‘personalities’ can to some extend be avoided. Nevertheless, as Jung observed as well, this is not a one-time process, instead, since the unconscious continues to develop as well, independent of the conscious personality, this integration must be a continues process. By integrating these unconscious elements, the ego and the self will be able to align themselves to eachother: “The more numerous and the more significant the unconscious contents which are assimilated to the ego, the closer the approximation of the ego to the self even though this approximation must be a never-ending process.” (Aion, p.23) In a business such an integration would be comparable to a situation in which the goals and interests of the employees and the CEO are aligned. However, this must also be a never-ending process, since these goals and interests of these different actors will continue to change as well.

Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious

What are the Archetypes?

As already illustrated by the example of Philemon in part 1, Jung, while actively evoking fantasies and dreams, discovered that his unconscious was filled with multiple figures. Since Jung had a deep understanding of ancient myths, cultures and symbols, Jung discovered that there existed several similarities between the figures and fantasies which ‘inhabited’ Jung’s own unconscious, and the figures and fantasies which were represented within the myths and symbols of our ancient ancestors.

As such, Jung arrived at the conclusion that certain parts of our unconscious are collective, meaning that they already exist when an individual is born and that they share strong communalities with the unconscious of other individuals in the past, present, and future. At the same time, although they might be represented in varying ways, they are also similar across cultures and religions. These commonalties existing within the unconscious of every individual are what Jung defined as the archetypes of the collective unconscious: “Psychic existence can be recognized only by the presence of contents that are capable of consciousness […] the contents of the collective unconscious […] are known as archetypes.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.4) As such, the archetypes can be seen as universal images and symbols which originate from the collective unconscious and are recognizable to people without requiring any initial explanation. In this sense, similar to instinct, people are born with a capacity to understand the archetypes; they are not required to be taught to someone.

Different Archetypes: Personal, Modified & Dogmatic

Jung observed that the archetypes of the collective unconscious can manifest themselves in distinct forms. On the one hand there exist archetypes which have, in a way, been more developed and have in this sense become a part of the conscious characteristics of a culture. They are, for instance, expressed in myths, fairy tales and traditions. Since these archetypes have been made conscious to a certain degree, it is also easier to pass them on to future generations through these traditions: “Primitive tribal lire is concerned with archetypes that have been modified in a special way. They are no longer contents of the unconscious, but have already been changed into conscious formulae taught according to tradition.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.5)

On the other hand, there exist archetypes which have a more personal nature and are more influenced by the nature of an individual’s private personality; they have not been modified by a culture. As a result of their individual nature, these archetypes are also a lot easier to define, as compared to the modified cultural archetypes:

“Their immediate manifestation, as we encounter it in dreams and visions, is much more individual, less understandable, and more naïve than in myths, for example. The archetype is essentially an unconscious content that is altered by becoming conscious and by being perceived, and it takes its colour from the individual consciousness in which it happens to appear.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.5)

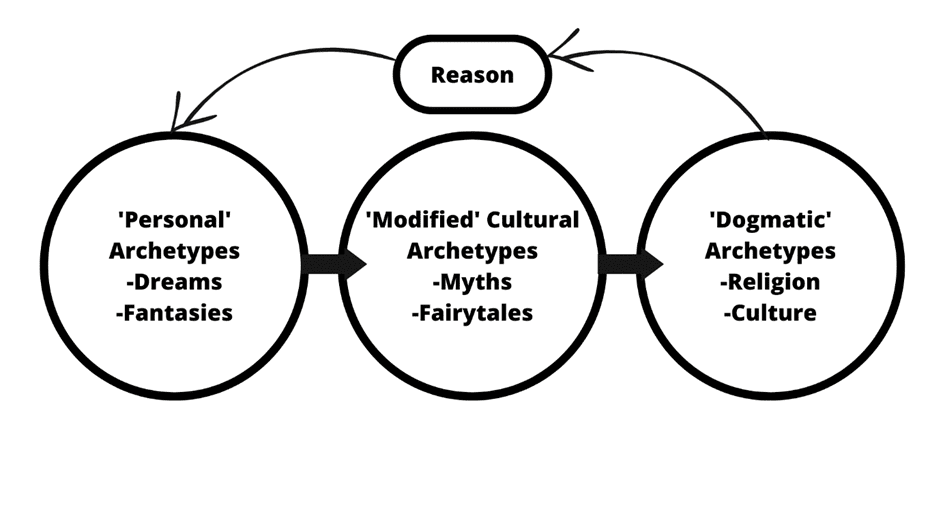

I believe that this difference can be illustrated by the figure below. On the left side we have the personal archetypes, which differ for each individual; although the dreams and fantasies represented by these kinds of archetypes may have their origin within the collective unconscious, the personality of the individual influences the representation of these archetypes (Dreams & fantasies).

In the middle we have the modified cultural archetypes. It is possible to argue that these archetypes originate from many individuals of a community having similar personal archetypes. These similar personal archetypes may result in the development of myths and symbols, for instance. As a result, they are no longer a part of the unconscious world, but have been made conscious.

In case this development continues, it is possible that the modified cultural archetypes develop into dogmatic archetypes, such as a religion. In this case, the archetypes have become conscious to such a degree that it is not often observed that these archetypes developed from the personal unconscious. Jung observed this as well in relation to the Catholic religion:

“Dogma takes the place of the collective unconscious by formulating its contents on a grand scale. The Catholic way of life is completely unaware of psychological problems in this sense. Almost the entire life of the collective unconscious has been channelled into the dogmatic archetypal ideas and flows along like a well-controlled stream in the symbolism of creed and ritual.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.12)

As such, Jung argued that religious ideas originated from symbols and images which had their origin within the collective unconscious of the individual. The idea that the ‘the Kingdom of God is within you’ would therefore be true in this sense. This individual nature of religion has, however, been ‘forgotten’ by most dogmatic religions.

The End of an Archetype

Interestingly, as Jung observed as well, in case the archetypes have become too conscious, they might end up losing their meaning all together. As Jung indicated, archetypical symbols are extremely meaningful; meaningful to such an extent that no one even considers questioning their meaning: “The fact is that archetypal images are so packed with meaning in themselves that people never think of asking what they really do mean.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.13) However, as soon as humans start to question the meaning of archetypes, it is possible that ‘gods die’, according to Jung, because their apparent lack of meaning is exposed: “That the gods die from time to time is due to man’s sudden discovery that they do not mean anything, that they are made by human hands, useless idols of wood and stone.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.13) As Jung observed, if this happens, reason is the culprit, since, through reason, it is concluded that the archetypes do not mean anything at all: “He has merely discovered that up till then he has never thought about his images at all. And when he starts thinking about them, he does so with the help of what he calls reason – which in point of fact is nothing more than the sum total of all his prejudices and myopic views.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.13) Jung used the Protestant revolution as an example; all the images and icons were destroyed because of their uselessness from a perspective based upon reason.

As a result, we return to the circle on the left in the figure above, where the archetypes, especially in the West, are once again mostly personal and unconscious. Jung indicated, however, that individuals often still seek meaningful images and symbols, which might explain the interest in Eastern religion, for example:

“The Protestant is cast out into a state of defencelessness that might well make the natural man shudder. His enlightened consciousness, of course, refuses to take cognizance of this fact, and is quietly looking elsewhere for what has been lost in Europe. We seek the effective images, the thought-forms that satisfy the restlessness of heart and mind, and we find the treasures of the East.” (The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p.13)

At the same time, this might also explain why Jung’s ideas interest us as much as they do; they as well, satisfy a certain restlessness by pointing us to the symbols and images hidden deep within the unconscious.

Now that it has been discussed what an archetype is, how they evolve, and how they can eventually become meaningless through reason, it is interesting to discuss some examples of archetypes as well. For this purpose, I have selected two of the most interesting archetypes: the hero archetype and the archetypal image of God.

In order to illustrate the archetype of the hero it is extremely useful to turn to the works of Joseph Campbell. Fundamentally, Campbell has successfully built on Jung’s idea of the archetypes, most notably through his analyses of the hero archetype. Like Jung, Campbell noticed that, throughout every hero myth existing within the world, the hero follows a similar pattern: departure, initiation, and return:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.” (Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, p.23)

In this way, the journey of the hero is not just a personal journey, but a universal one. Every individual can relate to the journey of the hero and does usually not question the existence of heroes. At the same time, the journey of the archetypal hero is, as indicated by Campbell, similar across cultures. Even heroes in movies go through similar journeys as heroes in ancient myths. The hero from the Lord of the Rings movies, Frodo, is one such example. Frodo, who is at first hesitant to submit to the call to adventure, eventually, with the aid of other supernatural characters, crosses the first threshold to the other world. Frodo leaves the safe and comfortable world of the Shire and goes on an adventure to Mordor. Throughout this adventure he has to face many challenges and overcome many temptations. Eventually Frodo returns to the Shrine, and he becomes a master of two worlds.

If we follow the stories of heroes of ancient myths or fairy tales, they follow the similar paths as the heroes of these modern movies. Joseph Campbell provided a few examples of such ancient hero myths:

“Prometheus ascended to the heavens, stole fir from the gods, and descended. Jason sailed through the Clashing Rocks into a sea of marvels, circumvented the dragon that guarded the Golden Fleece, and returned with the fleece and the power to wrest his rightful throne from a usurper. Aeneas went down into the underworld, crossed the dreadful river of the dead, threw a sop to the three-headed watchdog Cerberus, and conversed, at last, with the shade of his dead father.” (The Hero with a Thousand Faces, p.23)

As a result, whether we are dealing with heroes present within Greek mythology (Prometheus, Jason, and Aeneas), or heroes from present-day movies or books, they follow the same path of departure, initiation, and return. At the same time, even though these heroic journeys are definitely not unique, they continue to resonate with us, even after thousands of years, because they represent archetypal images and symbols with which we can identify.

Another example of an archetype is the idea of God. As Jung observed, the idea of the existence of God has already been ingrained in the psyche before the development of consciousness. As such, everyone has a pre-existing notion of what it means to believe in a God and, at the same time, every individual has the capability to believe in God: “If, therefore, we speak of ‘God’ as an ‘archetype’, we are saying nothing about His real nature but are letting it be known that ‘God’ already has a place in that part of our psyche which is pre-existent to consciousness.” (Memories, Dreams, Reflections, p.407) This would also explain why almost all existing cultures have developed a relationship with a God, albeit in different forms.

These and many other examples pointed Jung to the existence of certain universal images existing deep down within the psyche of every individual, which Murray Stein defined as: “More or less invariant universal fantasies and patterns of behavior (the archetypes) in an area of the deep psyche that he [Jung] called the “collective unconscious.”” ( Murray Stein, Jung’s Map of the Soul, p.4)

The Soul

In essence, what Jung documented throughout the Red Book and the Black Books, was an encounter with his own soul. Jung defined the soul in the Red Book, and as you can see, the soul, as Jung defined it, is quite comprehensive:

“I, your soul, am your mother, who tenderly and frightfully surrounds you, your nourisher and corrupter; I prepare good things and poison for you […] I am your body, your shadow, your effectiveness in this world, your manifestation in the world of the Gods, your effulgence, your breath, your odor, your magical force.” (The Red Book, p.582)

In this sense, the soul is the source of life which fills one’s psyche. Therefore, someone who lacks feelings, interests, or overall energy, is often considered to be ‘soulless’. Since Jung’s exploration of his own soul forms the most important part of everything which he documented in the Black Books and the Red Book, the soul is discussed at greater length in the following chapters.

Defining the soul for our business metaphor is a bit more complicated. Essentially, when we think of a business that lacks ‘soul’, we can consider a business that lacks energy, motivation, and the ability to innovate. Soulless businesses can still exist for a long time and be relatively successful, however, they do not produce anything unique, and most employees will not enjoy working for such a business, unless they themselves lack soul.

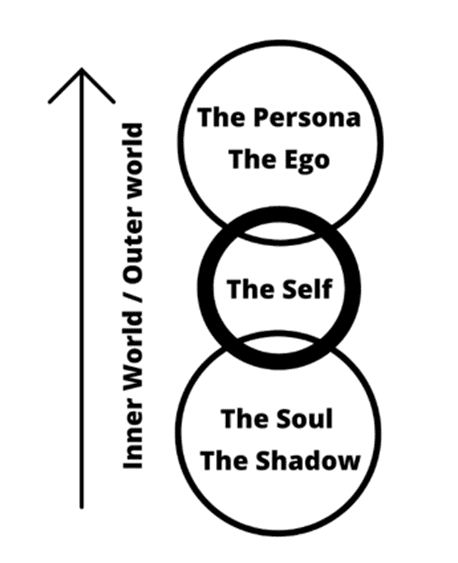

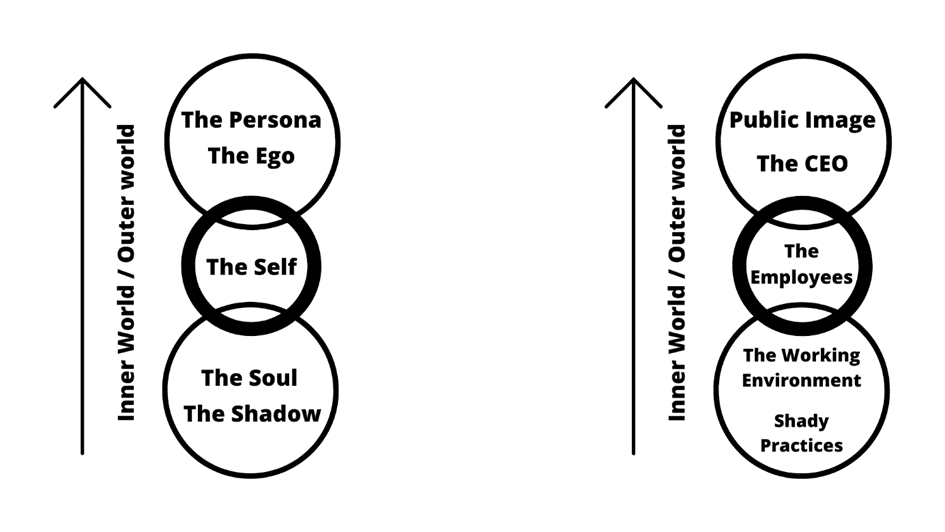

In the figure below you can see all the definitions discussed so far, the psyche on the left, and the business on the right. The higher up on the arrow in the figure, the more this part is shown to the outside world, the lower on the arrow, the less this part is shown to the world, but also the less it is shown to the conscious self without first making considerable efforts at making these parts conscious.

Conclusions to Part 2

In this second article, some of the more unconscious parts of the psyche are explored; the unconscious itself, the archetypes, and the soul. Later, in article three, the more ‘dangerous’ and hidden aspects of the psyche are addressed: the shadow, the anima, and the animus. In case you do not want to miss the next part, you can subscribe to my newsletter or youtube channel.