Table of Contents

A Summary and Analysis of Carl Jung’s Aion

Introduction

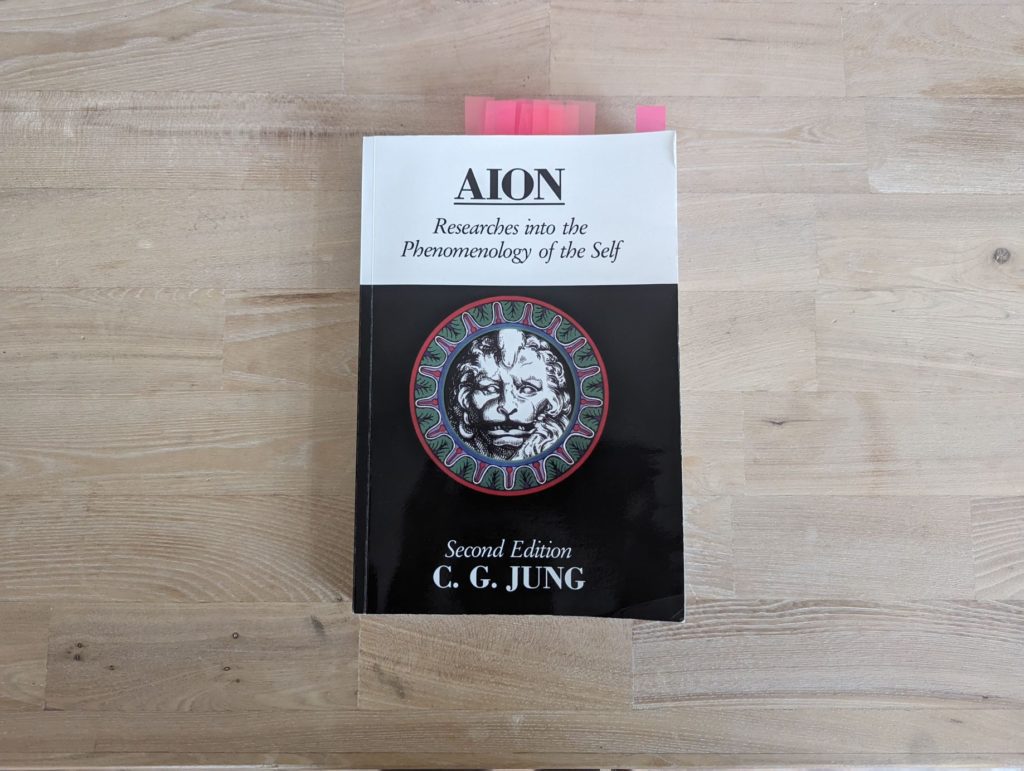

Dr. Jordan Peterson said the following about a book written by Carl Jung called Aion: “If you want to have nightmares for the rest of your life, that’s a really good book to read. I mean, that book just terrified me.” In case you prefer not to have nightmares for the rest of your life, but still want to know what Carl Jung’s Aion is all about, then this summary and analysis of Aion might be for you. I have sacrificed my own sleep by reading Aion, so that you do not have to do so.

Jung and Aion: The Ego

Published in 1951, Aion is one of Carl Jung’s most important works from his later years. The title Aion is derived from the Greek word Aeon, referring to the age (aeon) of Christianity. Throughout Aion Jung discussed the collective psychic development represented by the Christian era. What makes Aion such a scary book? Aion is mostly considered to be a scary book because it deals with the unknown and the consequences which we will inevitably face if we do not want to come to understand the unknown.

Jung observed that our ego (our conscious personality), rests upon conscious and unconscious content. Jung observed that this content can be divided into three categories: (1) ‘temporarily subliminal contents’, referring to our memory, which consists of the content which our mind can reproduce voluntarily. (2) ‘Unconscious contents that cannot be reproduced voluntarily’. (3) ‘Contents that are not capable of becoming conscious at all.’ (Aion, p.4)

Categories 2 and 3 are the categories that might scare us, and rightly so. The unconscious content of category 2 may spontaneously reveal itself to the conscious mind which, depending on its content, may, as discussed later in this analysis, severely disrupt the relatively peaceful and stable state of the conscious mind. Category 3 is, as Jung observed, hypothetical. However, its existence is a logical conclusion from the existence of categories 1 and 2. Category 3 exists of the content which is yet to be revealed to the ego, or content which may never reveal itself. Essentially, Jung argued that our mind is full of content of which we are not consciously aware, which may or may not at any point in time reveal itself.

Our ego is therefore vulnerable to these revelations from the unconscious. Jung argued that our ego does not represent our entire personality, for the unconscious elements represented by categories 2 and 3 are missing: “The ego is never more and never less than consciousness as a whole.” (p.5) At the same time, Jung observed that a complete description of one’s ego-personality remains impossible, since the contents of the unconscious cannot be grasped fully. This is a rather scary conclusion, because Jung believed that, despite being largely unknown, these unconscious elements might be the most important defining characteristics of our personality: “This unconscious portion, as experience has abundantly shown, is by no means unimportant. On the contrary, the most decisive qualities in a person are often unconscious and can be perceived only by others, or have to be laboriously discovered with outside help.” (p.5)

Jung and Aion: The Self

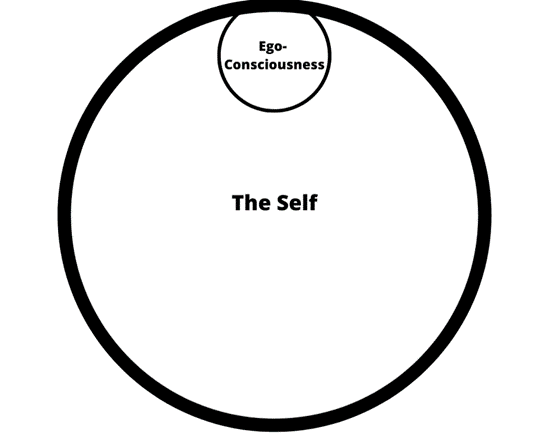

Jung called the combination of the conscious elements (the ego), with the unconscious elements, the Self. The self therefore represents the entirety of our personality, which, as we can conclude from the arguments above, can never be fully known; it can never be fully conscious. This is where Aion becomes an even scarier book (and we are only on page 5). Jung argued that the existence of categories 2 and 3 has a significant impact on our free will; our ability to make our own choices:

“The ego is, by definition, subordinate to the self and is related to it like a part to the whole. Inside the field of consciousness it has, as we say, free will. […] But, just as our free will clashes with necessity in the outside world, so also it finds its limits outside the field of consciousness in the subjective inner world, where it comes into conflict with the facts of the self.” (p.5)

Similar to external events occurring which impact our freedom, such as a storm preventing us from being able to go to the beach, Jung argued that internal events may also inhibit us from doing what we want. In this sense an ‘internal storm’ may prevent us from going to the beach. Moreover, to make matters worse for the ego, Jung argued that the unconscious characteristics of our personality, can be altered completely through the unconscious content of the self, without our ego having any influence over the matter: “It is indeed well known that the ego not only can do nothing against the self, but is sometimes actually assimilated by unconscious components of the personality that are in the process of development and is greatly altered by them.” (p.6)

As a result, although our ego forms the centre of our conscious personality, it is arguably not the centre of our entire personality, since here it might clash with the unconscious elements of the self. Jung observed that it is impossible to determine to what degree the ego is dependent upon the unconscious personality, however, according to Jung, we should in no instance underestimate this dependence.

Jung and Aion: The Shadow

At this point you may be wondering what content is hiding within the unconscious. Jung divided the unconscious into two categories: (1) the personal unconscious, which is developed throughout a person’s life, and (2) the collective unconscious, which is already present when an individual is born. Jung called the content of the collective unconscious ‘the archetypes of the collective unconscious’. Jung considered three archetypes to have the most influence on the ego; the shadow, the anima, and the animus: “The archetypes most clearly characterized from the empirical point of view are those which have the most frequent and the most disturbing influence on the ego. These are the shadow, the anima, and the animus.” (p.8)

Of these archetypes, Jung considered the shadow to be the easiest to observe and experience, since the shadow can be deducted from the content of the personal unconscious. The shadow consists of the darker characteristics of the individual’s personality, as such, since the individual and the ego, as well as the individual’s environment, do not like these characteristics, they have been repressed into the individual’s unconscious.

As a result, Jung observed that it takes considerable effort to become conscious of one’s shadow. However, this is a significant step necessary to become aware of one’s complete self: “To become conscious of it [the shadow] involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge, and it therefore, as a rule, meets with considerable resistance.” (p.8)

The shadow can be used to illustrate the impact the unconscious may have on our free will, from a conscious perspective. According to Jung, the darker characteristics of an individual’s personality, together forming the shadow, are emotional in nature: “They have an emotional nature, a kind of autonomy, and accordingly an obsessive or, better, possessive quality.” (p.8) This is the case according to Jung because emotions are not an activity in which the individual engages, instead, emotions are something which ‘happens’ to the individual, outside of the individual’s conscious influence. In this instance, Jung observed that the individual is a ‘passive victim’ of these emotions.

Jung also observed that, luckily, the content of the shadow, which forms a kind of ‘lower level of personality’, can be integrated into the conscious personality, albeit with significant effort. A way in which the shadow can be observed, and therefore eventually integrated, is through the way in which the content of the shadow projects itself upon the environment of the individual. In this case, the emotional nature of the shadow reveals itself due to the fact that the individual believes that an emotional response is the result of events occurring outside of the individual; in other people for instance: “In this case both insight and good will are unavailing because the cause of the emotion appears to lie, beyond all possibility of doubt, in the other person” (p.9)

Instead, however, the emotional response resulting from the observation of behaviour of ‘the other person’, is the result of a projection of the individual’s own shadow. For instance, in case a person becomes extremely annoyed when someone behaves impatiently, the emotional response (being annoyed), is not the result of the behaviour of the other person, instead, it is caused by a projection of the shadow. The person him or herself is in this case secretly (even to the individual him or herself) impatient. In this case the individual meets its own shadow in the form of the other person and, instead of confronting the shadow within, might confront the other person.

Jung further elaborated that the individual does not consciously engage in creating these projections, instead, these projections are created outside of the individual’s conscious control, at least as long as the shadow is not integrated into the individual’s consciousness: “As we know, it is not the conscious subject but the unconscious which does the projecting. Hence one meets with projection, one does not make them.” (p.9) As a result of this, the individual, as indicated by Jung, will have a ‘fake’ relationship with its environment:

“The effect of projection is to isolate the subject from his environment, since instead of a real relation to it there is now only an illusory one. Projections change the world into the replica of one’s own unknown face. In the last analysis, therefore, they lead to an autoerotic or autistic condition in which on dreams a world whose reality remains forever unattainable.” (p.9)

It will then become increasingly more difficult for the conscious ego personality to observe the illusory world it has created. Essentially, the individual is then interacting with the world through glasses which show the world in a way which is not real. The glasses are created and put on unconsciously by the ego, and the longer one wears these glasses, the hard it becomes to take them off and face reality.

Jung and Aion: The Anima and Animus

To a certain extent, these projections belong to the world of the shadow. Although extremely difficult, with significant moral effort these can be revealed to the individual’s ego, because they are a result of a person’s own inferior personality.

However, as Jung argued, after a certain moment, these projections even extend beyond the individual’s own negative personality. Instead, their source may be found in figures and symbols which represent the opposite sex of the individual, the anima in man and the animus in woman. Jung observed that the anima and animus are archetypes a lot further removed from an individual’s conscious personality, as compared to the shadow. As such, they are almost impossible to comprehend: “It is quite within the bounds of possibility for a man to recognize the relative evil of his nature, but it is a rare and shattering experience form him to gaze into the face of absolute evil.” (p.10

Jung used the concepts Eros (love) and Logos (reason) to illustrate the significance of the Anima and Animus. Jung made the generalization that the conscious personality of a woman is more often than not characterized by “the connective quality of Eros than by the discrimination and cognition associated with Logos” (p.14), whereas, in a man, “Eros, the function of relationship, is usually less developed than Logos.” (p.14)

However, although not usually a part of a man’s conscious personality, Eros still exists within a man, whereas Logos still exists within a woman. As a result, since these are not developed properly and therefore essentially exist in a more primitive form within the individual’s unconscious, they may project themselves upon the environment of the individual in an unrefined manner. In such a case, Jung believed that a man becomes ‘anima-possessed’, and a woman becomes ‘animus-possessed’. When this occurs, it might happen that, when a man and woman interact with eachother while they are ‘possessed’, they are essentially interacting with an inferior form of the characteristics of the opposite sex, i.e. a woman might act overly aggressive through her animus, whereas a man might act extremely seductive through his animal “When animus and anima meet, the animus draws his sword of power and the anima ejects her poison of illusion and seduction.” (p.15) Men may then become possessed by an irrational temper, whereas women may become possessed by irrational beliefs: “It seems a very natural state of affairs for men to have irrational moods and women irrational opinions.” (p.17)

Jung further argued that, whereas the contents of the anima and animus may be made conscious, the anima and animus themselves, being archetypes, cannot be made conscious. However, by being aware of the anima and animus, and by integrating the contents produced by these archetypes, they can play an important role as a compensatory force:

“It is, in fact, one of the most important tasks of psychic hygiene to pay continual attention to the symptomatology of unconscious contents and processes, for the good reason that the conscious mind is always in danger of becoming one-sided, of keeping to well-worn paths and getting stuck in blind alleys.” (p.20)

As such, a man can develop his Eros by paying attention to the content of his unconscious, whereas a woman can develop her Logos in the same way. Instead of a man then becoming possessed by an inferior form of his Eros, he can use it as a compensatory force when his Logos dominates his conscious mind. Alternatively, instead of a woman becoming possessed by an inferior form of Logos, she can, after studying the content of her animus carefully, use her Logos as a compensatory factor when her Eros dominates her conscious mind.

Jung and Aion: The Integration of the Unconscious

After discussing these archetypes of the unconscious throughout the first chapters of Aion, Jung turned to the following question: what happens to the conscious ego personality when the contents of the unconscious are integrated?

Jung believed that, when content is integrated into the ego, the ego may become more powerful and regain some of its free will, i.e. it becomes less likely for the ego to become dominated by the contents of the unconscious, since the ego is aware of its existence after it has successfully integrated some of the unconscious content: “The more numerous and the more significant the unconscious contents which are assimilated to the ego, the closer the approximation of the ego to the self.” (p.23)

Jung warned us of two extremes in relation to the integration of the unconscious. On the one hand, it is possible that the ego becomes assimilated into the self. If this occurs, then the ego comes under the control of the unconscious and a certain ‘eternal dream -state’ may be the consequence, resulting from the fact that the conscious ego personality is not sufficiently rooted in the real world. Essentially, there is then not enough order in the conscious world to counteract the chaos emerging from the unconscious world. On the other hand, it is also possible that the self becomes assimilated to the ego. In such a case “room must be made for the dream at the expense of the world of consciousness.” (p.25) Here there is perhaps too much order in the conscious world whereby there is no room at all for some of the chaos existing within the unconscious world to reveal itself.

The second situation, where the unconscious is essentially suppressed, may not appear to be as bad as the first situation, where the unconscious swallows up the ego. However, although perhaps not resulting in immediate negative consequences, it may have serious negative consequences in the long run: “The will can control them only in part. It may be able to suppress them, but it cannot alter their nature, and what is suppressed comes up again in another place in altered form, but this time loaded with a resentment that makes the otherwise harmless natural impulse our enemy.” (p.27)

Jung and Aion: Christ, a Symbol of the Self

After the discussion of the ego, the self, and the archetypes of the shadow and the anima/animus, as well as a discussion on the integration of these archetypes, Jung commenced a discussion on Christ and the Antichrist. Jung saw Christ, as an important “living myth of our culture” (p.36) who, real or not, “exemplifies the archetype of the self.” (p.37)

Christ Himself, as a symbol, is not complete because He does not embody the darker side of the self, instead, the darker side is attributed to a separate entity, the devil: “The Christ-symbol lacks wholeness in the modern psychological sense, since it does not include the dark side of things but specifically excludes it in the form of a Luciferian opponent.” (p.41) The Church attempted to solve this problem through the Privatio Boni doctrine, which essentially states that evil is not a thing in itself, instead, evil is simply the lack of good.

As Jung argued, when we consider Christ as a symbol of the self, then its is possible to see the Antichrist as the inferior part of the self, i.e. the shadow, which opposes the Christian concept of Christ, where, resulting from the Privatio Boni doctrine, the Antichrist is separated from Christ:

“In the empirical self, light and shadow form a paradoxical unity. In the Christian concept, on the other hand, the archetype is hopelessly split into two irreconcilable halves, leading ultimately to a metaphysical dualism – the final separation of the kingdom of heaven from the fiery world of the damned.” (p.42)

Jung observed that this dualism makes the Antichrist a complicated problem for Christianity. However, when seeing Christ as a symbol of the self, it represents only one half, the good half, as such, the Antichrist can just as much be seen as a symbol of the self, except that it represents the evil half.

Therefore, Jung did not agree with the idea of the Privatio Boni. Jung argued that evil is only all to real and that many historic, as well as current events proof that evil is not simply the absence of good: “One could hardly call the things that have happened, and still happen, in the concentration camps of the dictator states an “accidental lack of perfection” – it would sound like mockery.” (p.53) Although evil is therefore real, what is good and what is evil is dependent upon the subjective and conscious experience of the psyche. The unconscious, as Jung observed, does not differentiate between good and evil. Despite the subjective nature, however, Jung stressed that the existence of evil should not be questioned: “Today as never before it is important that human beings should not overlook the danger of the evil lurking within them. It is unfortunately only too real, which is why psychology must insist on the reality of evil and reject any definition that regards it as insignificant or actually non-existent.” (p.53)

Jung concluded his discussion in Aion on ‘Christ as a symbol of the self’, by indicating the important difference between perfection and completeness. Christ, in a religious sense, is equal to perfection, whereas, as a symbol of the self, Christ represents completeness, without being perfect: “Like the related ideas of atman and tao in the East, the idea of the self is at least in part a product of cognition, grounded neither on faith nor on metaphysical speculation but on the experience that under certain conditions the unconscious spontaneously brings forth an archetypal symbol of wholeness.” (p.69)

According to Jung, the individual who has experienced such completeness, is more than ever aware of his or her own imperfection. This is the case because with this completeness comes the recognition of the evil residing in the self; an awareness of the shadow: “If he voluntarily takes the burden of completeness on himself he need no find it “happening” to him against his ill in a negative form. This is as much as to say that anyone who is destined to descend into a deep pit had better set about it with all the necessary precautions rather than risk falling into the hole backwards.” (p.70)

Jung warned us that in case we do not take the burden of completeness upon ourselves, meaning if we do not voluntarily integrate our unconscious personality, including its darker aspects, the world will remain a victim of our projections: “The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate. That is to say, when the individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner opposite, the world must perforce act out the conflict and be torn into opposing halves.” (p.71)

Jung and Aion: Faith vs Science

Later on in Aion Jung explained the problematic situation which has arisen from the development of a division between faith and knowledge in the eighteenth century. Whereas faith is not capable of explaining all that is happening within the world, science is not capable of explaining all that is happening within the psyche: “Faith lacked experience and science missed out the soul. Instead, science believed fervently in absolute objectivity and assiduously overlooked the fundamental difficulty that the real vehicle and begetter of all knowledge is the psyche, the very thing that scientists knew the least about.” (p.173)

Jung further argued that our increased focus on science and technology, at the expense of faith, tradition and symbols, may lead to ‘spiritual regression’. This is the case according to Jung because traditions, for instance, lose their importance and are pushed into the world of the unconscious. As such, they are no longer capable of compensating rational scientific ideas, whereby mass psychosis might be the outcome: “Loss of roots and lack of tradition neuroticize the masses and prepare them for collective hysteria.” (p.181)

In order to treat this collective hysteria, Jung warned us that civil liberties may be abolished in order to deal with the hysteria on a collective scale: “Collective hysteria calls for collective therapy, which consists in abolition of liberty and terrorization. Where rationalistic materialism holds sway, states tend to develop less into prisons than into lunatic asylums.” (p.181)

In this sense, an important compensatory force, which was rooted in myths, mysteries, symbols, and tradition, has been slowly eroding over the last few decades. Without this root, which essentially forms a bridge between the conscious and the unconscious world, there is not much left which can protect the ego from adopting ‘unsound ideas’, according to Jung.

“The ever-widening split between conscious and unconscious increases the danger of psychic infection and mass psychosis. With the loss of symbolic ideas the bridge to the unconscious has broken down. Instinct no longer affords protection against unsound ideas and empty slogans. Rationality without tradition and without a basis in instinct is proof against no absurdity.” (p.248)

Conclusions

Is Aion one of the scariest books ever written? Hopefully you can, after reading this summary and analysis of some of the most important ideas from Carl Jung’s Aion, decide this for yourself. In my opinion Aion represents an important warning left to us by Carl Jung about what could happen if we ignore an important and defining part of our self, the unconscious.

Even though the unconscious is filled with those things which we might not want to see, such as the contents of the shadow and anima/animus archetypes, it is important to recognize that evil is also a part of the world, and also a part of us. Only by voluntarily engaging with these darker aspects of our ‘lower personality’ can we learn to understand and manage these powerful forces.

What do you think; is Aion one of the scariest books ever written?