Table of Contents

Introduction

Synchronicity is a rather mysterious and complicated principle developed by Carl Jung. Throughout this article it is explained what Jung meant when he wrote about synchronicity and why the synchronicity principle may be interesting in helping us understand events occurring within the world.

For his psychological practice, Carl Jung was once visited by a young female patient who, as Jung observed, was ‘psychologically inaccessible’. As Jung indicated, she knew everything better and her extreme rationality prevented Jung from making any progress with her treatment. Jung hoped that something would happen which would break her wall, making treatment possible: “I had to confine myself to the hope that something unexpected and irrational would turn up, something that would burst the intellectual retort into which she had sealed herself.” (p.109)

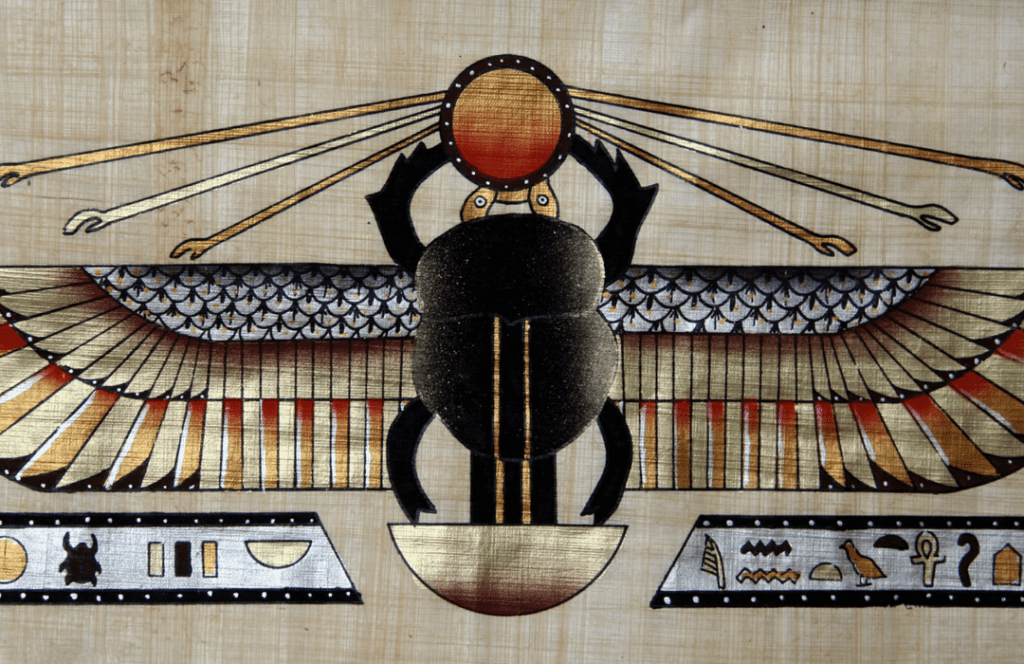

Jung’s wish was swiftly granted. Jung’s patient was sharing an intense dream she had during which someone had given her a golden scarab. While she was sharing her dream, Jung noted that a large insect was knocking against the window from the outside. This was strange since the room was dark and therefore of not much interest to this insect.

Jung opened the window and caught the insect, a large beetle, as it flew inside. The gold-green insect looked like the closest local resemblance of a golden scarab and when Jung gave the insect to his patient saying, “here is your scarab”, the patient dropped her defences, leading to a successful continuation of the treatment.

Synchronicity

Throughout the eight volume of the Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Jung shared several of such stories. Are such occurrences coincidence or is something else going on?

Jung indicated that he often observed such phenomenon, which he would later call synchronicity, within his own live, as well as within the experiences of many of his patients. Jung observed that most of his patients did not like to share these experiences with the outside world, for fear of being ridiculed: “I was amazed to see how many people have had experiences of this kind and how carefully the secret was guarded. So my interest in this problem has a human as well as scientific foundation.”(p.4)

Fundamentally, Jung developed the synchronicity principle to explain events and experiences which cannot be explained by causality; these events require a principle beyond causality in order to understand their occurrence. As discussed later in this article, the existence of such a phenomenon has far-reaching implications for the place of our psyche within the world.

Natural Law

As Jung observed, modern science has made us consider natural law as the governing principle of all that happens within the world: for example, natural law may define that a certain event, event ‘A’, will always result in event ‘B’, whereas event ‘C’, can never result in event ‘A’. However, how can it then be explained that, on some occasions, event ‘C’ does result in event ‘A’?

As Jung argued, the principle underlying the statistical truths of natural law, causality, cannot explain these events. As such, Jung argued that another principle must exist which can explain such acausal events: “The connection of events may in certain circumstances be other than causal, and requires another principle of explanation.” (p.5) Jung called this ‘other principle of explanation’ synchronicity. You may wonder, however, what proof exists that such a principle may be real.

Jung indicated that, in order to answer this question, we must separate acausal events from causal events: we should be looking for events which cannot be explain causally but can also not be explained by mere chance. Events which are highly unlikely, but can still be explained by chance, should, as such, also be excluded.

Chance and Synchronicity

Jung, for example, indicated that if, on a certain day, the number of one’s train ticket, the number of an incoming phone call, and the number of one’s seat number in the cinema are all strikingly similar, we might be tempted to consider these events acausal. However, Jung observed that, although highly rare, such an occurrence may still be explained by causality and chance. As such, Jung did not consider such an event to be explainable through the synchronicity principle.

The term synchronicity may, however, be applied to instances were even chance cannot ultimately explain the apparent lack of causality: “In such circumstances we are inclined to say, “That cannot be mere chance,” without knowing what exactly we are saying.” (p.10) According to Jung, as soon as such an event exceeds the limits of chance, we might determine that there exists a ‘meaningful cross-connection’, i.e. synchronicity.

Moreover, as discussed in more detail later in this article, in order for there to exist a ‘meaningful cross-connection’, the external event must in some way be linked to the internal world of the psyche. For instance, in the example of a similar number appearing multiple times throughout the day, this event may nevertheless be considered synchronistic, according to Jung, in case the individual experiencing the event had a previous internal experience in relation to the number.

An example may be a profound dream during which the number also appeared multiple times. If this happens, a causal explanation becomes impossible, and synchronicity may be used to explain such an occurrence.

As Jung elaborated, the apparent inexplicability of such events results from the reality that such events cannot be explained in rational terms: “As I have already said, however, their “inexplicability” is not due to the fact that the cause is unknown, but to the fact that a cause is not even thinkable in intellectual terms.” (p.103)

However, as Jung also observed, these difficulties when it comes to explaining such events may also be a direct result of our unlimited confidence in causality: “It is only the ingrained belief in the sovereign power of causality that creates intellectual difficulties and makes it appear unthinkable that causeless events exist or could ever occur.” (p.102)

Space, Time, and the Psyche

In such an instance, Jung believed that there exists an ‘elastic’ connection between the psyche and space and time: “Rhine’s experiments show that in relation to the psyche space and time are, so to speak, “elastic” and can apparently be reduced almost to vanishing point, as though they were dependent on psychic conditions and did not exist in themselves but were only “postulated” by the conscious mind” (p.19)

Before elaborating on ‘Rhine’s experiments’ to which Jung is here referring, it is interesting to elaborate on the connection between space and time. Jung argued that space and time have only become definite concepts in the course of the mental development of humanity. Essentially, as Jung argued “space and time consists of nothing” (p.20), they are merely a product of the psyche. The concept of space and time, as Jung observed, may therefore have merely been developed to satisfy the needs of he who wants to explain the world: “If space and time are only apparently properties of bodies in motion and are created by the intellectual needs of the observer, then their relativization by psychic conditions is no longer a matter of astonishment but is brought within the bounds of possibility.” (p.20)

The experiments conducted by J.B. Rhine illustrated this point, according to Jung: “The possibility presents itself when the psyche observes, not external bodies, but itself. […] it is a product of pure imagination, of “chance’ ideas which reveal the structure of that which produces them, namely the unconscious.” (p.20)

Rhine’s Experiments

What then are the experiments carried out by Rhine? Essentially, Rhine conducted experiments to investigate the potential existence of extrasensory perception (ESP). To conduct his experiments, Rhine would lay out a pack of 25 cards, which he divided into 5 groups of 5 cards. Each of these groups of 5 cards consisted of cards with 5 different symbols. As such, each card within the group of 5 cards was unique.

In each experiment these cards were laid down 800 times in front of an individual who was then asked to guess the symbol on the cards without seeing the symbol. The expected result based on probability was that the subjects would guess, on average, 1 correct card out of each 5 cards; meaning 5 correct cards of the entire pack of 25 cards.

However, the average after conducting the experiment numerous times was 6.5 correct cards out of the 25 cards of each pack. As Jung observed, this was impressive: “The probability of a chance deviation of 1.5 amounts to only 1 in 250.000.” (p.107) Some subjects even guessed the cards correctly in more than double the probable situations. One subject even guessed all 25 cards correctly.

Even when Rhine conducted the same experiments with the subjects being far removed from him and the table of cards (up to 4000 miles), the results remained the same. Rhine then conducted another type of experiment whereby he would not lay the cards down until after the subject had made his guesses; sometimes waiting up to two weeks after the subject had guessed the cards. The results coming out of this experiment had a probability of 1 in 400.000.

A third experiment consisted of subjects attempting to influence the results of mechanically thrown dices, which also had impressive results. As Jung observed, these experiments illustrated that the psyche may be able to surpass space and time constraints:

“The result of the spatial experiments proves with tolerable certainty that the psyche can, to some extent, eliminate the space factor. The time experiment proves that the time factor […] can become physically relative. The experiment with dice proves that moving bodies too, can be influenced psychically.” (p.108)

Although such conclusions may be hard to believe, Jung himself was not surprised, since he believed that space and time were concepts which existed in close relationship to the psyche.

Synchronicity and the Psyche

Before getting too excited, however, it must be noted that Rhine’s experiments have been criticised heavily, and that other researchers were not able to reproduce the results of Rhine. Jung, however, merely used the experiments done by Rhine to attempt to find a scientific bases for his own rather mysterious experiences, as well as the experiences of many of his patients, such as the experience with the golden scarab discussed in the introduction. At the same time, however, Jung himself observed that these would not be sufficient to convince anyone of the existence of synchronicity.

Throughout the eight volume of his Collected Works, Jung shared some other examples of such ‘coincidences’. As Jung observed, after carefully examining such examples, the phenomena Jung discussed in relation to synchronicity can be grouped into three categories:

“1. The coincidence of a psychic state in the observer with a simultaneous, objective, external event that corresponds to the psychic state or content (e.g., the scarab) […] 2. The coincidence of a psychic state with a corresponding (more or less simultaneous) external event taking place outside the observer’s field of perception, I.e., at a distance, and only verifiable afterward […] 3. The coincidence of a psychic state with a corresponding, not yet existent future event that is distant in time and can likewise only be verified afterward.” (p.110)

As such, synchronicity can be seen as the connection between a certain state of the psyche and the occurrence of an external event which corresponds closely to the state of the psyche: “Synchronicity therefore consists of two facts: a) An unconscious image comes into consciousness either directly (i.e., literally) or indirectly (symbolized or suggested) in the form of a dream, idea, or premonition. b) An objective situation coincides with this content.” (p.31) In the case of the scarab, the unconscious image consists of the intense dream experienced by Jung’s patient, whereas the beetle which flew into the room represents the coinciding objective situation.

The question then remains, according to Jung, how (and wherefrom) the initial unconscious image arises, as well as how the coinciding objective situation arises.

Jung himself hinted to an answer to this question. Jung believed that the archetypes of the collective unconscious (a detailed explanation of the archetypes can be found here: The Archetypes) may play a role in synchronistic events. According to Jung, when consciousness is suppressed to a certain degree, the unconscious may ‘slip into the space vacated.’ (p.20) Jung believed that many examples of synchronistic events reveal their archetypal nature. The scarab, for instance, is an archetypal symbol of rebirth.

Conclusions

In order to explain the idea of synchronicity Jung relied heavily on the experiments carried out by Rhine. However, as indicated, these experiments have become seriously disputed years after Jung used them to argue in favour of the existence of synchronicity. As such, there remains no scientific evidence pointing to the existence of the synchronicity principle.

What remains of proof of the existence of this principle is limited. Jung shared several anecdotal examples, such as the example of the golden scarab discussed in this article. As a result, it is largely up to us to decide whether we believe that synchronicity exists or not. Perhaps you can remember some examples from your own life, or perhaps some events may occur in the future which cannot be explained by mere causality. In these instances, it may be interesting to see whether the idea of synchronicity can offer an explanation.

Jung himself, although a serious believer in synchronicity, could not establish whether such events are frequent or not. Jung believed that they are extremely rare, but also argued that they may appear more frequently than what we may expect.

If synchronicity indeed exists, Jung observed that the consequences are far reaching: “They prove that a content perceived by an observer can, at the same time, be represented by an outside event, without any causal connection. From this it follows either that the psyche cannot be localized in space, or that space is relative to the psyche.” (p.115)